A Brief History of the Dead, Kevin Brockmeier

A Brief History of the Dead, Kevin Brockmeier

A Brief History of the Dead was one of the more frustrating reading experiences I’ve had. (No, not because it totally ripped off the title of a short story I wrote years and years ago.) It’s one of those novels where you are constantly, painfully reminded of how good it could have been had the author not made some initial grave misstep. Here, that misstep was including the even-numbered chapters.

Let me explain. It’s a novel with a very cool premise, which is why I picked it up in the first place. The odd-numbered chapters chronicle the lives of residents of the city of the dead. That’s where you go, the novel claims, after you die, and there you remain until every person who knew you has died. At that point, you disappear, and that part of the afterlife is a mystery to the folks who live (?) in the city of the dead.

As the novel starts out, the population of the city (and therefore the city itself, as it has elastic properties) is growing exponentially thanks to a world that has evidently gone down the tubes—lots of wars, and lots of biological warfare. That’s what turns out to be the kicker: a manmade disease nicknamed “the Blinksâ€, which kills very, very rapidly and to which no one seems to be immune. After only a few weeks, the city has shrunk to a very small number of people—all of the people who knew the one remaining survivor, a biologist-type named Laura something.

I’m just going to say it: Laura something is not very interesting. Turns out she’s alive because she got sent out to Antarctica to do some research for Coca-Cola. (Let me reveal a really annoying plot twist: Coca-Cola, in an incredibly lazy turn of events, is responsible for the distribution of the virus that kills everybody. Now, I hate that company as much as every other good liberal, but come on.) Since she’s all isolated and stuff, she doesn’t get the Blinks. We then have to spend the even-numbered chapters reading the tedious details of Laura’s life and eventual doomed journey across the continent to find other survivors, most of which have been lifted from other, better books about Antarctica. (This will bother you less, probably, if you have devoted less time to reading about that awesomely barren place than I have.) She’s not a very interesting character, though that’s not all her fault—it’s hard to put her story up against the story of the city, which is infinitely more moving, thoughtful, lovely. In Laura’s chapters, we read rehashed descriptions of isolation in a cold climate; in the other chapters, we get haunting, original, beautifully written accounts of what it’s like to exist on the other side, what it’s like to be bound to every person—right down to the street cleaner—Laura something has ever met.

So anyway: the odd-numbered chapters are, on the whole, stunningly beautiful and surprising. (You can read the particularly beautiful and surprising first chapter here.) But Laura is dull, and the Coca-Cola conspiracy is trite and irritating, and so in the end I recommend this book with a great deal of hesitation. Honestly, if you just go read the first chapter you’ll have got the best of it.

In short: I’d give it two stars out of five. If you really want to read it, get it from the library rather than buying it, and if you get tired of Laura just start skipping her chapters.

Read it if you like: Post-apocalyptic fiction, An Inconvenient Truth

Don’t take my word for it:Â Apex Blog, LitMob, Wendy Palmer

The Last Boleyn, Karen Harper

The Last Boleyn, Karen Harper

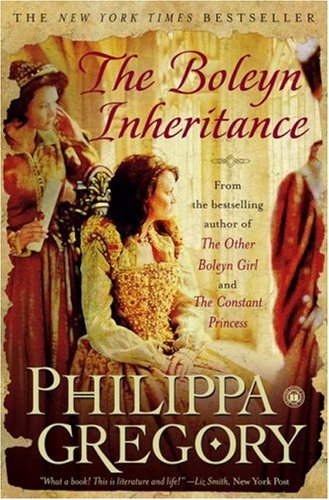

The Boleyn Inheritance

The Boleyn Inheritance The Secret Bride

The Secret Bride The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay Northline

Northline The Dead Fathers Club

The Dead Fathers Club A Brief History of the Dead

A Brief History of the Dead Star Wars: Legacy of the Force: Invincible

Star Wars: Legacy of the Force: Invincible